Modulnavigering

Denne modulen inneholder enkle navigasjonsverktøy som hjelper deg med å finne frem. Her er noen ikoner du bør se etter:

Generell navigasjon

Interaktive elementer

Frem og tilbake for å se gjennom bildene

Dra til siden

Klikk for neste

Bruk plussikonet til å åpne popup-vinduer med tilleggsinformasjon

Klikk for neste visning

Lukk popup-vinduer for å gå tilbake til hovedbildet

Skift mellom visninger

Klikk for mer informasjon

Modulnavigering

Velkommen til den første undervisningsmodulen i MS Elevate - en serie på flere moduler som omhandler multippel sklerose og relaterte temaer. Den er forfattet av sykepleiere til sykepleiere.

Denne modulen setter fokus på:

Sykdomsaktivitet og progresjon

Patofysiologi

Tegn og symptomer på progresjon

Screeningverktøy

Attakk monitorering

MR oppfølging

Samtaler om progresjon

Oppsummering og hovedpunkter

Etter hver undervisningdel kan en sjekke hva en har lært ved å gjennomgå en kunnskapstest.

Referanser er oppført både under hvert bilde og oppsummert avslutningsvis.

Å gjenkjenne aktivitet/progresjon

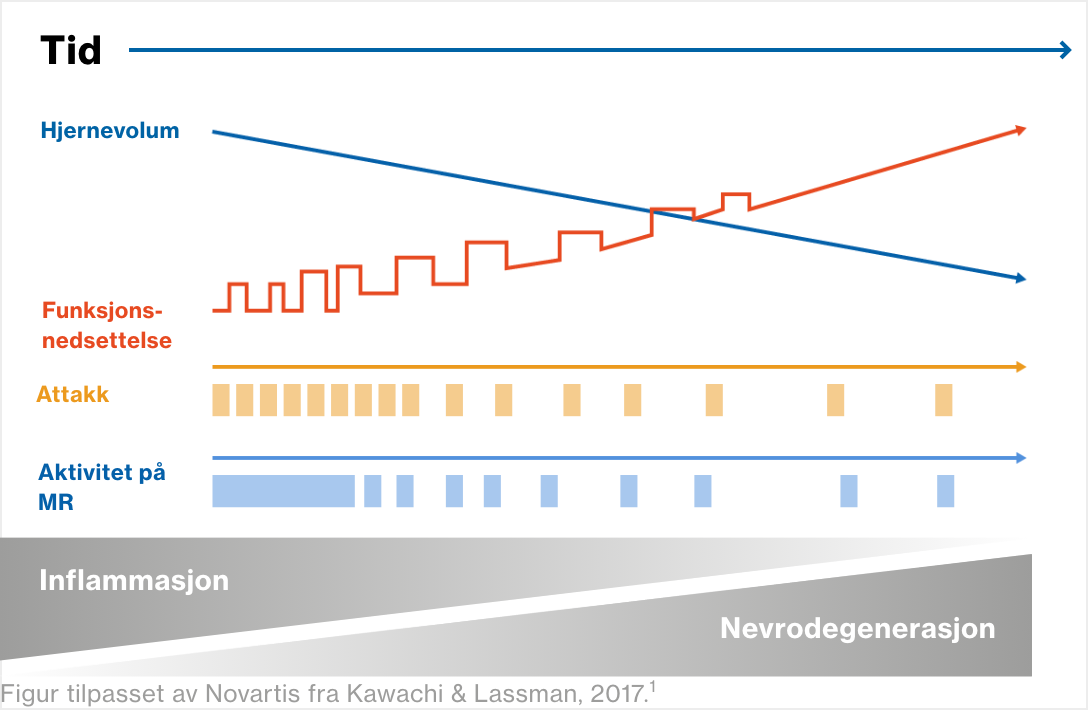

Multippel sklerose er en autoimmun sykdom som rammer sentralnervesystemet og forårsaker akkumulerende funksjonsnedsettelse1

I begynnelsen forekommer det mest inflammasjon, men over tid oppstår det mer nevrodegenerasjon1.2

og økt funksjonsnedsettelse uavhengig av akutte attakk (tilbakefall eller forverringer).3

For mer informasjon om hvordan akkumulerende funksjonsnedsettelse vurderes klinisk, se senere bilder i denne modulen og se modul 3: Vurdering av MS-pasienter.

Lesjoner i hjerne og ryggmarg samt tap av hjernevolum (atrofi) kan ses på MR-undersøkelser (magnetresonanstomografi). For mer informasjon, se senere bilder i denne modulen, og se modul 3: Vurdering av MS-pasienter.

Referanser

- Kawachi I, Lassmann H. Neurodegeneration in multiple sclerosis and neuromyelitis optica. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2017;88:137–145.

- Dobson R, Giovannoni G. Multiple sclerosis – a review. Eur J Neurol. 2019;26:27–40.

- Scalfari A, et al. The natural history of multiple sclerosis, a geographically based study 10: relapses and long-term disability. Brain. 2010:133;1914–1929.

Å gjenkjenne aktivitet/progresjon

MS kan være aktiv i alle stadier, uavhengig av progresjon, også før diagnose1,2

Tegn på tidlig sykdomsaktivitet er sett hos personer som ennå ikke har fått en MS-diagnose, men som har radiologisk isolert syndrom (RIS) eller klinisk isolert syndrom (CIS).

Bekreftet MS kan være aktiv i alle stadier, uavhengig av sykdomsprogresjon / progresjon av funksjonsnedsettelse.

Dette er MS-undertypene, ofte kalt 2013-klassifiseringen.1 Klikk på de blå boksene for fiktive kasushistorier

RRMS – Ikke aktiv3

Anne er 24 år gammel og ble henvist til nevrolog for mer enn syv år siden med en historie med migrene. MR-bildene viste en unormal endring i hvit substans som var periventrikulær. Ett år senere rapporterte hun om nedsatt syn ledsaget av øyesmerter (høyre øye) i fem dager, og seks måneder etter dette hadde hun en firedagers episode med svakhet i venstre ben. Begge de akutte anfallene gikk over ved hjelp av intravenøs metylprednisolon. Hun har ikke hatt noen ytterligere attakk de siste seks årene. I løpet av denne perioden har de årlige MR-undersøkelsene ikke vist nye MS-lesjoner, og det har ikke vært noen klinisk progresjon verken ved fysiske undersøkelser eller selvrapportering.

Referanser

- Lublin FD, et al. Defining the clinical course of multiple sclerosis: the 2013 revisions. Neurology. 2014;83:278–286.

- Klineova S, Lublin FD. Clinical course of multiple sclerosis. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Med. 2018;8:a028928.

- Pasientkasus: Illustrative fictional case.

Å gjenkjenne aktivitet/progresjon

MS-behandling har som mål å beskytte den nevrologiske reserven1,2

Referanser

- Giovannoni G, et al. Brain health: time matters in multiple sclerosis. Mult Scler Relat Disord. 2016;9 Suppl 1:S5–S48.

- Leino-Kilpi, Helena et.al. Elements of Empowerment and MS Patients. Journal of Neuroscience Nursing, vol.30, no.2, Apr. 1998 pp.116+

Å gjenkjenne aktivitet/progresjon

Tidlig intervensjon med sykdomsmodifiserende terapier (DMT) er viktig.1-5

Figur tilpasset av Novartis fra Giovannoni G, et al. Mult Scler Rel Disord 2016:9:S5‒S8

Referanser

- Giovannoni G, et al. Brain health: time matters in multiple sclerosis. Mult Scler Rel Disord. 2016:9:S5‒S8.

- Rocca MA, et al. Evidence for axonal pathology and adaptive cortical reorganization in patients at presentation with clinically isolated syndromes suggestive of multiple sclerosis. Neuroimage 2003;18:847–855.

- De Stefano N, et al. Assessing brain atrophy rates in a large population of untreated multiple sclerosis subtypes. Neurology. 2010;74:1868–1876.

- Merkel B, et al. Timing of high-efficacy therapy in relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis: a systematic review. Autoimmun Rev. 2017;16:658–665.

- Brown JWL, et al. Association of initial disease-modifying therapy with later conversion to secondary progressive multiple sclerosis [published correction appears in JAMA. 2020:7;323:1318]. JAMA. 2019;321:175–187.

Patofysiologi

Flere patologiske prosesser bidrar til nevrodegenerasjon

Autoimmune prosesser forårsaker patologiske endringer i CNS. Inflammasjon starter tidlig i sykdomsforløpet:

Til slutt fører progressivt tap av demyeliniserte aksoner til akselerert tap av hjernevev ‒ hjerneatrofi.4

Figur utarbeidet av Novartis på bakgrunn av Chari DM. Remyelination in multiple sclerosis. Int Rev Neurobiol. 2007;79:589–6202

Referanser

- Joy JE, Johnston RB Jr., editors. Multiple Sclerosis: Current Status and Strategies for the Future. Washington (DC): National Academies Press (US); 2001: pp. 43, 60.

- Chari DM. Remyelination in multiple sclerosis. Int Rev Neurobiol. 2007;79:589–620.

- Oh J, et al. Diagnosis and management of secondary-progressive multiple sclerosis: time for change. Neurodegener Dis Manag. 2019;9:301–317.

- Wang C, et al. Lesion activity and chronic demyelination are the major determinants of brain atrophy in MS. Neurol Neuroimmunol Neuroinflamm. 2019;6:e5933.

- Joy JE, Johnston RB Jr., editors. Multiple Sclerosis: Current Status and Strategies for the Future. Washington (DC): National Academies Press (US); 2001: pp. 43, 56, 57, 60, 243.

Patofysiologi

PPMS

PPMS

Aktive lesjoner er sjeldne2

Hjerneatrofi er vanlig2

Mindre inflammasjon enn ved RRMS3

Lesjoner som blir større over tid2

Aktivitering av mikrogliale celler (immunceller i CNS) i normal grå og hvit substans er fremtredende2

Der er lesjoner i hjernen og ryggmargen, men i motsetning til RRMS er der mer sannsynlig at de er begrenset til ryggmargen4

RRMS

RRMS

Aktivt demyeliniserende plakk er den mest fremtredende typen lesjon2

Flere nye hjernelesjoner (plakk) enn ved PPMS5

Lesjoner av typen inflammatorisk demyelinering, 2 og flere inflammatoriske lesjoner enn ved PPMS,3,5

Aksonal transseksjon (brudd på axoner) er vanlig2

Det er lesjoner i hjernen og ryggmargen, men i motsetning til PPMS er det mer sannsynlig at de er begrenset til hjernen4

SPMS

SPMS

Hjerneatrofi i grå substans spiller en sentral rolle i progresjon av funksjonsnedsettelse, og driver irreversibel akkumulering av funksjonsnedsettelse6,7 og bidrar til kognitiv svikt8

Referanser

- Kanavos P, et al. Towards better outcomes in multiple sclerosis by addressing policy change: The International MultiPlE Sclerosis Study (IMPrESS). 2016. Available at: http://www.lse.ac.uk/business-and-consultancy/consulting/consulting-reports/towards-better-outcomes-in-ms. Accessed: January 2021.

- Macaron G, Ontaneda D. Diagnosis and management of progressive multiple sclerosis. Biomedicines. 2019;7:56.

- National Multiple Sclerosis Society. (A) Primary Progressive MS. Available at: https://www.nationalmssociety.org/What-is-MS/Types-of-MS/Primary-progressive-MS. Accessed: January 2021.

- Dastagir A, et al. Brain and spinal cord MRI lesions in primary progressive vs. relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis. eNeurologicalSci. 2018;12:42–46.

- National Multiple Sclerosis Society (B). Relapsing Remitting MS. Available at: https://www.nationalmssociety.org/What-is-MS/Types-of-MS/relapsing-remitting-MS. Accessed: January 2021.

- Fisher E, Lee JC, Nakamura K, Rudick RA. Gray matter atrophy in multiple sclerosis: a longitudinal study. Ann Neurol. 2008;64:255–265.

- Calabrese M, et al. The changing clinical course of multiple sclerosis: a matter of gray matter. Ann Neurol. 2013;74:76–83.

- Amato MP, et al. Association of neocortical volume changes with cognitive deterioration in relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis. Arch Neurol. 2007;64:1157–1161.

Tegn og symptomer på progresjon

Mange med MS opplever etter hvert progressiv nevrologisk funksjonsnedsettelse

Ved PPMS er det pågående progresjon av funksjonsnedsettelse fra starten av, men det er perioder med stabilitet, slik det er ved SPMS1

Ved progressiv MS kan noen ganger en person få midlertidig forbedret skår på funksjonsskalaen EDSS2, for eksempel etter å ha begynt med fysioterapi

Figur utarbeidet av Novartis på bakgrunn av Kurtzke JF. Rating neurologic impairment in multiple sclerosis: an expanded disability status scale (EDSS). Neurology. 1983;33:1444–1452 2

Referanser

- Klineova S, Lublin FD. Clinical course of multiple sclerosis. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Med. 2018;8:a028928

- Kurtzke JF. Rating neurologic impairment in multiple sclerosis: an expanded disability status scale (EDSS). Neurology. 1983;33:1444–1452.

Tegn og symptomer på progresjon

Progresjon kan omfatte mange symptomer og er ulik fra pasient til pasient1-6

Du finner mer informasjon om symptomer og hvordan de vurderes og behandles i modul 2 til 5.

Referanser

- Scalfari A, et al. Onset of secondary progressive phase and long-term evolution of multiple sclerosis. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 2014;85:67‒75.

- National MS Society (NMSS). Multiple Sclerosis: Just the Facts. NMSS; 2018 Available at https://www.nationalmssociety.org/nationalmssociety/media/msnationalfiles/brochures/brochure-just-the-facts.pdf. Accessed: December 2020.

- Papathanasiou A, et al. Cognitive impairment in relapsing remitting and secondary progressive multiple sclerosis patients: efficacy of a computerized cognitive screening battery. ISRN Neurol. 2014;2014:151379.

- Gross HJ, Watson C. Characteristics, burden of illness, and physical functioning of patients with relapsing-remitting and secondary progressive multiple sclerosis: a cross-sectional US survey. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat. 2017;13:1349–1357.

- Beiske AG, et al; Nordic SPMS study group. Health-related quality of life in secondary progressive multiple sclerosis. Mult Scler. 2007;13:386‒392.

- Ziemssen T, et al. A mixed methods approach towards understanding key disease characteristics associated with the progression from RRMS to SPMS: Physicians’ and patients’ views. Mult Scler Relat Disord. 2020;38:101861.

Screeningsverktøy

Screeningsverktøy som evaluerer flere symptomer, kan bidra til å følge opp progresjon av funksjonsnedsettelse over tid

En signifikant utfordring når man skal overvåke progresjon ved MS, er vanskeligheter med å kvantifisere funksjonsnedsettelse over tid.1 Eksempler på screeningverktøy er:

Referanser

- Ontaneda D, Fox RJ. Progressive multiple sclerosis. Curr Opin Neurol. 2015;28:237–243.

- Kurtzke JF. Rating neurologic impairment in multiple sclerosis: an expanded disability status scale (EDSS). Neurology. 1983;33:1444–1452.

- Fischer JS, et al. Multiple Sclerosis Functional Composite (MSFC). Administration and Scoring Manual. New York: National Multiple Sclerosis Society, 2001. Available at: https://www.nationalmssociety.org/NationalMSSociety/media/MSNationalFiles/Brochures/10-2-3-31-MSFC_Manual_and_Forms.pdf.

- Thompson H, Mauk KL (Eds). Nursing management of the patient with multiple sclerosis. AANN and ARN Clinical Practice Guideline Series, 2011. Available at: http://iomsn.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/07/AANN-ARN-IOMSN-MS-Guideline_FINAL.pdf. Accessed: September 2020.

Oppfølging av attakker (1/3)

Attakk indikerer underliggende sykdomsaktivitet og kan forutsi progresjon av funksjonsnedsettelse1

Et attakk er en forbigående klinisk episode av sykdomsaktivitet som innebærer inflammasjon og/eller aktiv demyelinisering:2

Manglende bedring etter attakker ved RRMS er forbundet med kortere tid til progresjon til SPMS3

Attakker før og etter progresjon akselererer tiden til alvorlig funksjonsnedsettelse (EDSS 6) ved progressiv MS4

Selv om de fleste attakker etterfølges av klinisk remisjon, kan noen symptomer vedvare og bidra til progresjon av funksjonsnedsettelse5

Figur tilpasset av Novartis fra Soldán MMP, et al. Neurology 2015;84:81–88.4

Referanser

- Giovannoni G, et al. Brain health: time matters in multiple sclerosis. Mult Scler Rel Disord 2016:9:S5‒S8.

- Kalincik T. Multiple sclerosis relapses: epidemiology, outcomes and management. A systematic review. Neuroepidemiology 2015;44:199–214.

- Novotna M, et al. Poor early relapse recovery affects onset of progressive disease course in multiple sclerosis [published correction appears in Neurology. 2015 Oct 13;85:1355]. Neurology. 2015;85:722–729.

- Soldán MMP, et al. Relapses and disability accumulation in progressive multiple sclerosis. Neurology. 2015;84:81–88.

- Leray E, et al. Evidence for a two-stage disability progression in multiple sclerosis. Brain. 2010;133:1900–13.

Magnetresonanstomografi (MR) (1/8)

MR-oppfølging sørger for bevis på aktiv sykdom

Fokale lesjoner på MR er det patologiske kjennetegnet på MS1 som forekommer i hjernen og ryggmargen:1,2

Hjerne-MR er abnormal hos nesten alle personer med etablert MS og

80 % av de som har CIS2Lesjoner i ryggmargen forekommer hos >80 % av personer med etablert MS og opptil 50 % av personer med CIS (vanligvis cervikalt)2

Nye hjernelesjoner oppdages 10 ganger oftere enn attakk oppstår,3 noe som gjør at hjerne-MR er svært følsom for overvåking av sykdomsaktivitet.4 I tillegg kan lesjonsbelastning brukes som en prediktor for langsiktig progresjon av funksjonsnedsettelse4

Referanser

- Sastre-Garriga J, et al. MAGNIMS consensus recommendations on the use of brain and spinal cord atrophy measures in clinical practice. Nat Rev Neurol. 2020;16:171–182.

- Brownlee WJ, et al. The diagnosis and differential diagnosis of multiple sclerosis: progress and challenges. Lancet. 2017; 389: 1336–1346.

- Dobson R, Giovannoni G. Multiple sclerosis – a review. Eur J Neurol. 2019;26:27–40.

- Wattjes MP, et al. Evidence-based guidelines: MAGNIMS consensus guidelines on the use of MRI in multiple sclerosis – establishing disease prognosis and monitoring patients. Nat Rev Neurol. 2015;11:597–606.

- Lublin FD, et al. Defining the clinical course of multiple sclerosis: the 2013 revisions. Neurology. 2014;83:278–286

Snakke om progresjon

Sykepleiere spiller en viktig rolle når det gjelder å snakke om progresjon

Sykepleiere spiller en viktig rolle når det gjelder å gi støtte til pasienter og deres omsorgspersoner i forbindelse med diagnostisering av SPMS ved å sørge for:1

Opplæring

Oppmuntring

Psykososial støtte og støtte av egenbehandling

En motvekt til misoppfatninger knyttet til SPMS og behandling av denne formen for MS

Diskusjon om aktiv vs. inaktiv sykdom kan få betydning her fordi det har innvirkning på DMT-behandling.

Referanser

- Oh J, et al. Diagnosis and management of secondary-progressive multiple sclerosis: time for change. Neurodegener Dis Manag. 2019;9:301–317.

Referanser

- Amato MP, et al. Association of neocortical volume changes with cognitive deterioration in relapsing–remitting multiple sclerosis. Arch Neurol. 2007;64:1157–1161.

- Bar-Or A. The immunology of multiple sclerosis. Semin Neurol. 2008;28:29–45.

- Bartley AJ, et al. Genetic variability of human brain size and cortical gyral patterns. Brain. 1997;120:257–269.

- Barulli D, Stern Y. Efficiency, capacity, compensation, maintenance, plasticity: emerging concepts in cognitive reserve. Trends Cogn Sci. 2013;17:502–509.

- Behrangi N, et al. Mechanism of siponimod: anti-inflammatory and neuroprotective mode of action. Cells. 2019;8:24.

- Beiske AG, et al. Nordic SPMS study group. Health-related quality of life in secondary progressive multiple sclerosis. Mult Scler. 2007;13:386‒392.

- Bogosian A, et al. Multiple challenges for people after transitioning to secondary progressive multiple sclerosis: a qualitative study. BMJ Open 2019;9:e026421.

- Bonzano L, et al. Brain activity pattern changes after adaptive working memory training in multiple sclerosis. Brain Imaging Behav. 2020;14:142–154.

- Braley TJ, Chervin RD. Fatigue in multiple sclerosis: mechanisms, evaluation, and treatment. Sleep. 2010;33:1061–1067.

- Brown JWL, et al. for the MSBase Study Group. Association of initial disease-modifying therapy with later conversion to secondary progressive multiple sclerosis [published correction appears in JAMA. 2020:7;323:1318]. JAMA. 2019;321:175–187.

- Brownlee WJ, et al. The diagnosis and differential diagnosis of multiple sclerosis: progress and challenges. Lancet. 2017;389:1336–1346.

- Burke T, et al. The evolving role of the multiple sclerosis nurse. An international perspective. Int J MS Care. 2011;13:102–112.

- Calabrese M et al. The changing clinical course of multiple sclerosis: a matter of gray matter. Ann Neurol. 2013;74:76–83.

- Chari DM. Remyelination in multiple sclerosis. Int Rev Neurobiol. 2007;79:589–620.

- Claes N, et al. B cells are multifunctional players in multiple sclerosis pathogenesis: insights from therapeutic intervention. Front Immunol. 2105;6:642.

- Claflin SB, et al. The effect of disease modifying therapies on disability progression in multiple sclerosis: a systematic overview of meta-analyses. Front Neurol. 2019 Jan 10;9:1150.

- Copaxone Summary of Product Characteristics. Teva Pharmaceuticals Ltd, Castleford. 2003. Available at: https://www.medicines.org.uk/emc/product/183#gref

- Costello K, Kalb R. The use of disease-modifying therapies in multiple sclerosis. Principles and current evidence. A consensus paper by the Multiple Sclerosis Coalition. 2019. Available at: https://www.nationalmssociety.org/NationalMSSociety/media/MSNationalFiles/Brochures/DMT_Consensus_MS_Coalition.pdf#page=28&zoom=100,80,202. Accessed: January 2021.

- Dastagir A, et al. Brain and spinal cord MRI lesions in primary progressive vs. relapsing–remitting multiple sclerosis. eNeurologicalSci. 2018;12:42–46.

- Davies F, et al. ‘You are just left to get on with it’: qualitative study of patient and carer experiences of the transition to secondary progressive multiple sclerosis. BMJ Open. 2015;5: e007674.

- Davies F, et al. The transition to secondary progressive multiple sclerosis: an exploratory qualitative study of health professionals' experiences. Int J MS Care. 2016;18:257–264.

- De Stefano N, et al. Assessing brain atrophy rates in a large population of untreated multiple sclerosis subtypes. Neurology. 2010;74:1868–1876.

- De Stefano N, et al. Establishing pathological cut-offs of brain atrophy rates in multiple sclerosis. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2016;87:93–99.

- Deibel F, et al. Patients’, carers’ and providers’ experiences and requirements for support in self-management of multiple sclerosis: a qualitative study. Eur J Person Centered Healthc. 2013;1:457–67.

- Dobson R, Giovannoni G. Multiple sclerosis – a review. Eur J Neurol. 2019;26:27–40.

- Duddy M, et al. The UK patient experience of relapse in Multiple Sclerosis treated with first disease modifying therapies. Mult Scler Relat Disord. 2014;3:450–456.

- Fischer JS, et al. Multiple Sclerosis Functional Composite (MSFC). Administration and Scoring Manual. New York: National Multiple Sclerosis Society, 2001. Available at: https://www.nationalmssociety.org/NationalMSSociety/media/MSNationalFiles/Brochures/10-2-3-31-MSFC_Manual_and_Forms.pdf.

- Fisher E, et al. Gray matter atrophy in multiple sclerosis: a longitudinal study. Ann Neurol. 2008;64:255–265.

- Freedman MS, et al. Treatment optimization in MS: Canadian MS Working Group Updated Recommendations. Can J Neurol Sci. 2013; 40: 307–323

- Garg N, Smith TW. An update on immunopathogenesis, diagnosis, and treatment of multiple sclerosis. Brain Behav. 2015;5:e00362.

- Giovannoni G, et al. Brain health: time matters in multiple sclerosis. Mult Scler Rel Disord. 2016:9:S5‒S8.

- Goodman AD, et al. Siponimod in the treatment of multiple sclerosis. Expert Opin Investig Drugs. 2019;28:1051–1057.

- Granziera C, Reich DS. Gadolinium should always be used to assess disease activity in MS – Yes. Mult Scler J. 2020;26:765–766.

- Gross HJ, Watson C. Characteristics, burden of illness, and physical functioning of patients with relapsing–remitting and secondary progressive multiple sclerosis: a cross-sectional US survey. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat. 2017;13:1349–1357.

- Häusser-Kinzel et al. The role of B cells and antibodies in multiple sclerosis, neuromyelitis optica, and related disorders. Front. Immunol. 2019:10:201.

- Hillman L. Caregiving in multiple sclerosis. Phys Med Rehabil Clin N Am. 2013;24:619–627

- Hobart J, et al. International consensus on quality standards for brain health-focused care in multiple sclerosis. Mult Scler. 2019;25:1809–1818.

- Horáková D, et al. CARE-MS I, CARE-MS II, and CAMMS03409 Investigators. Proportion of alemtuzumab-treated patients converting from relapsing–remitting multiple sclerosis to secondary progressive multiple sclerosis over 6 years. Mult Scler J Exp Transl Clin. 2020;6:2055217320972137.

- Janeway CA Jr, et al. Immunobiology: The Immune System in Health and Disease. 5th edition. New York: Garland Science; 2001.

- Joy JE, Johnston RB (Eds), Committee on Multiple Sclerosis: Current Status and Strategies for the Future, Board on Neuroscience and Behavioral Health. Multiple Sclerosis: Current Status and Strategies for the Future. Washington DC: National Academy Press, 2001: pp. 55, 60, 64, 81.

- Kalb R, et al. Recommendations for cognitive screening and management in multiple sclerosis care. Mult Scler. 2018;24:1665–1680.

- Kalincik T. Multiple sclerosis relapses: epidemiology, outcomes and management. A systematic review. Neuroepidemiology 2015;44:199–214

- Kanavos P, et al. Towards better outcomes in multiple sclerosis by addressing policy change: The International MultiPlE Sclerosis Study (IMPrESS). 2016. Available at: http://www.lse.ac.uk/business-and-consultancy/consulting/consulting-reports/towards-better-outcomes-in-ms. Accessed: January 2021.

- Kappus N, et al. Cardiovascular risk factors are associated with increased lesion burden and brain atrophy in multiple sclerosis. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2016;87:181–187

- Katz Sand I, et al. Diagnostic uncertainty during the transition to secondary progressive multiple sclerosis. Mult Scler. 2014;20:1654–1657.

- Kawachi I, Lassmann H. Neurodegeneration in multiple sclerosis and neuromyelitis optica. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2017;88:137–145.

- Klineova S, Lublin FD. Clinical course of multiple sclerosis. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Med. 2018;8:a028928

- Kurtzke JF. Rating neurologic impairment in multiple sclerosis: an expanded disability status scale (EDSS). Neurology. 1983;33:1444–1452.

- Lassmann H, et al. Progressive multiple sclerosis: pathology and pathogenesis. Nat Rev Neurol. 2012 Nov 5;8:647–56.

- Leray E, et al. Evidence for a two-stage disability progression in multiple sclerosis. Brain. 2010;133:1900–1913.

- Lorscheider J, et al. MSBase Study Group. Defining secondary progressive multiple sclerosis. Brain. 2016;139:2395–405.

- Lublin FD, et al. International Advisory Committee on Clinical Trials in MS. The 2013 clinical course descriptors for multiple sclerosis: a clarification. Neurology. 2020;94:1088–1092.

- Lublin FD, et al. Defining the clinical course of multiple sclerosis: the 2013 revisions. Neurology. 2014;83:278–286.

- Lublin FD, Reingold SC. Defining the clinical course of multiple sclerosis: results of an international survey. National Multiple Sclerosis Society (USA) Advisory Committee on Clinical Trials of New Agents in Multiple Sclerosis. Neurology. 1996;46:907–911.

- Macaron G, Ontaneda D. Diagnosis and management of progressive multiple sclerosis. Biomedicines. 2019;7:56.

- Mayzent Summary of Product Characteristics. Novartis Europharm Limited, Dublin, Ireland. 2020. Available at: https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/medicines/human/EPAR/mayzent#product-information-section. Accessed: December 2020.

- Meier DS, et al. Time-series modeling of multiple sclerosis disease activity: a promising window on disease progression and repair potential? J Am Soc Neurotherapeutics. 2007;4:485–498.

- Merkel B, et al. Timing of high-efficacy therapy in relapsing–remitting multiple sclerosis: a systematic review. Autoimmun Rev. 2017;16:658–665.

- Mitjana R, et al. Diagnostic value of brain chronic black holes on T1-weighted MR images in clinically isolated syndromes. Mult Scler. 2014;20:1471–17.

- Motl RW, et al. Promotion of physical activity and exercise in multiple sclerosis: Importance of behavioral science and theory. Mult Scler J Exp Transl Clin. 2018;4:2055217318786745.

- MS Living well: Understanding your MRI. Available at: https://www.mslivingwell.org/learn-more-about-ms/understanding-your-mri/. Accessed: January 2021.

- MS Trust. Secondary Progressive Multiple Sclerosis. 2018. Available at: https://support.mstrust.org.uk/file/SPMS-A5-Booklet-Oct-2018-FINAL-WEB.pdf. Accessed: January 2021..

- National Institute For Health And Care Excellence. Single Technology Appraisal. Siponimod for treating secondary progressive multiple sclerosis [ID1304]. NICE, 2020. Available at: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ta656/evidence/appraisal-consultation-committee-papers-pdf-8900479549. Accessed: December 2020.

- National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE). Multiple sclerosis in adults: management. Clinical guideline CG186. October 2014. www.nice.org.uk/guidance/cg186. Accessed: September 2020.

- National MS Society (NMSS). Multiple Sclerosis: Just the Facts. NMSS; 2018 Available at https://www.nationalmssociety.org/nationalmssociety/media/msnationalfiles/brochures/brochure-just-the-facts.pdf. Accessed: December 2020.

- National Multiple Sclerosis Society (A). Primary Progressive MS. Available at: https://www.nationalmssociety.org/What-is-MS/Types-of-MS/Primary-progressive-MS. Accessed: January 2021.

- National Multiple Sclerosis Society (B). Relapsing Remitting MS. Available at: https://www.nationalmssociety.org/What-is-MS/Types-of-MS/relapsing-remitting-MS. Accessed: January 2021.

- Novotna M, et al. Poor early relapse recovery affects onset of progressive disease course in multiple sclerosis [published correction appears in Neurology. 2015;85:1355]. Neurology. 2015;85:722–729.

- Ocrevus Summary of Product Characteristics. Roche Registration GmbH, Grenzach-Wyhlen Germany. 2020. Available at: https://www.medicines.org.uk/emc/product/8898#gref. Accessed: July 2020.

- Oh J, et al. Diagnosis and management of secondary-progressive multiple sclerosis: time for change. Neurodegener Dis Manag. 2019;9:301–317.

- O'Loughlin E, et al. The experience of transitioning from relapsing remitting to secondary progressive multiple sclerosis: views of patients and health professionals. Disabil Rehabil. 2017;39:1821–1828.

- Ontaneda D, Fox RJ. Progressive multiple sclerosis. Curr Opin Neurol. 2015;28:237–243.

- Papathanasiou A, et al. Cognitive impairment in relapsing remitting and secondary progressive multiple sclerosis patients: efficacy of a computerized cognitive screening battery. ISRN Neurol. 2014;2014:151379.

- Raz E, et al. Periventricular lesions help differentiate neuromyelitis optica spectrum disorders from multiple sclerosis. Mult Scler Int. 2014;2014:986923.

- Rocca MA, Filippi M. Functional MRI in multiple sclerosis. J Neuroimaging. 2007;17 Suppl 1:36S–41S.

- Rocca MA, et al. Evidence for axonal pathology and adaptive cortical reorganization in patients at presentation with clinically isolated syndromes suggestive of multiple sclerosis. Neuroimage. 2003;18:847–855.

- Ross AP (Ed.). The role of the MS Nurse in relapse assessment and management. In: Counseling Points. Enhancing Patient Communication for the MS Nurse, vol. 11. Ridgeway, NJ: Delaware Media Group, 2016.

- Rosso M, Chitnes T. Association between cigarette smoking and multiple sclerosis. A review. JAMA Neurol. 2020;77:245–253.

- Sammarco C, et al. Multiple Sclerosis: the nurse practitioner’s handbook. National MS Society (US), 2013, p.32.

- Sandroff BM, et al. Measurement and maintenance of reserve in multiple sclerosis. J Neurol. 2016;263:2158–2169.

- Sastre-Garriga J, et al. MAGNIMS consensus recommendations on the use of brain and spinal cord atrophy measures in clinical practice. Nat Rev Neurol. 2020;16:171–182.

- Scalfari A, et al. Onset of secondary progressive phase and long-term evolution of multiple sclerosis. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 2014;85:67‒75.

- Scalfari A, et al. The natural history of multiple sclerosis, a geographically based study 10: relapses and long-term disability. Brain. 2010:133;1914–1929.

- Scolding N, et al. Association of British Neurologists: revised (2015) guidelines for prescribing disease-modifying treatments in multiple sclerosis. Pract Neurol. 2015;15:273–279.

- Sicotte NL. Neuroimaging in multiple sclerosis: neurotherapeutic implications. Neurotherapeutics. 2011;8:54–62.

- Signals of change: recognising the early signs of progression to MS. October 2020. Available at https://www.acnr.co.uk/wp-content/uploads/2020/11/Novartis-Signals-of-Change-3.pdf. Accessed December 2020.

- Sinay V, et al. School performance as a marker of cognitive decline prior to diagnosis of multiple sclerosis. Mult Scler. 2015;21:945–952.

- Sintzel MB, et al. Vitamin D and multiple sclerosis: a comprehensive review. Neurol Ther. 2018;7:59–85.

- Solari A, et al. Conversion to secondary progressive multiple sclerosis: patient awareness and needs. results from an online survey in Italy and Germany. Front Neurol. 2019;10:916.

- Soldán MMP, et al. Relapses and disability accumulation in progressive multiple sclerosis. Neurology. 2015;84:81–88.

- Sumowski JF, et al. Cognition in multiple sclerosis: state of the field and priorities for the future. Neurology. 2018;90:278–288.

- Sumowski JF, et al. Brain reserve and cognitive reserve protect against cognitive decline over 4.5 years in MS. Neurology. 2014;82:1776–1783

- Sumowski JF, et al. Brain reserve and cognitive reserve in multiple sclerosis: what you've got and how you use it [published correction appears in Neurology. 2013;81:604]. Neurology 2013;80:2186–2193.

- Thompson H, Mauk KL (Eds). Nursing management of the patient with multiple sclerosis. AANN and ARN Clinical Practice Guideline Series, 2011. Available at: http://iomsn.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/07/AANN-ARN-IOMSN-MS-Guideline_FINAL.pdf. Accessed: September 2020.

- Tolley C, et al. A novel, integrative approach for evaluating progression in multiple sclerosis: development of a scoring algorithm. JMIR Med Inform. 2020;8:e17592.

- Trip SA, Miller DH. Imaging in multiple sclerosis. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2005;76 (Suppl 3):iii11–iii18.

- UCSF (University of California, San Francisco) MS-EPIC Team: Cree BA, et al. Long-term evolution of multiple sclerosis disability in the treatment era. Ann Neurol. 2016;80:499–510.

- UCSF MS-EPIC Team (University of California, San Francisco MS-EPIC Team), et al. Silent progression in disease activity-free relapsing multiple sclerosis. Ann Neurol. 2019;85:653–666.

- Wang C, et al. Lesion activity and chronic demyelination are the major determinants of brain atrophy in MS. Neurol Neuroimmunol Neuroinflamm. 2019;6:e5933.

- Wattjes MP, et al. Evidence-based guidelines: MAGNIMS consensus guidelines on the use of MRI in multiple sclerosis – establishing disease prognosis and monitoring patients. Nat Rev Neurol. 2015;11:597–606.

- Ziemssen T, et al. A mixed methods approach towards understanding key disease characteristics associated with the progression from RRMS to SPMS: Physicians' and patients' views. Mult Scler Relat Disord. 2020;38:101861.

- Zivadinov R, et al. Autoimmune comorbidities are associated with brain injury in multiple sclerosis. Am J Neuroradiol. 2016;37:1010–1016.

Kunnskapstest

Test din viten nedenfor